Introduction – a shocking forgotten story

This is the story of a most remarkable and shocking story recently discovered in the history of the Village of Welton le Marsh (also known interchangeably as Waletune, Welton, Welton in the Marsh) at the Southern tip of the Lincolnshire Wolds. The events are not recorded in any modern historical references, but can be found in three forgotten Victorian documents, confirmed by a letter from no lesser an eye witness than Oliver Cromwell. The story has lived on, unnoticed in the scars on local buildings and the folk tales of villagers.

The story answers an ancient mystery that come local people may have asked them selves – Welton church fell down before 1792, but why did it happen? The tale reveals a Nationally significant civil war battle in this village, bigger than the battle of Winceby in October 1643. This included two terrible massacres, one by the villagers of Welton le Marsh themselves.

A church of two halves

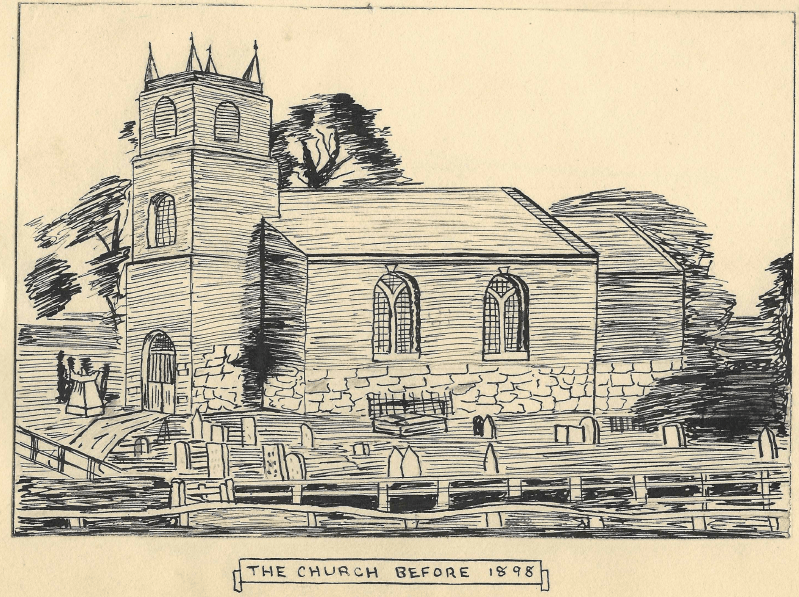

St Martin’s Church in Welton le Marsh is unusual in that it has a base of mediaeval chalk and sandstone blocks, with an upper half of Georgian brickwork. How did it come to be like this? Did some calamity befall it in the past?

Current appearance of Welton le Marsh church (2025) showing lower mediaeval stonework and upper Georgian brickwork.

Village stories

Since I arrived in the Welton le Marsh in 2021, many people have offered me small stories about the village’s history. Individually they were interesting, but collectively they hid a shocking nearly four hundred year old year story that had fallen from the public memory. This included revealing why the village church had fallen down. They include (paraphrased):

There is an interesting old building called Thwaite Hall in Welton Woods” – Paul Holden

Would you like to borrow a book on Welton le Marsh history?” – Trevor Oliver

The Church Steeple fell down in 1791 … on the almost entirely demolished church” – Arthur Hundleby

Hanby Hall was demolished in 1975 because as children we used to play in it and the owners were worried it was unsafe” – Tim Broughton

Why does my house (Thwaite Hall) look like it was built from the same stone as the church?” – Ed Roughton

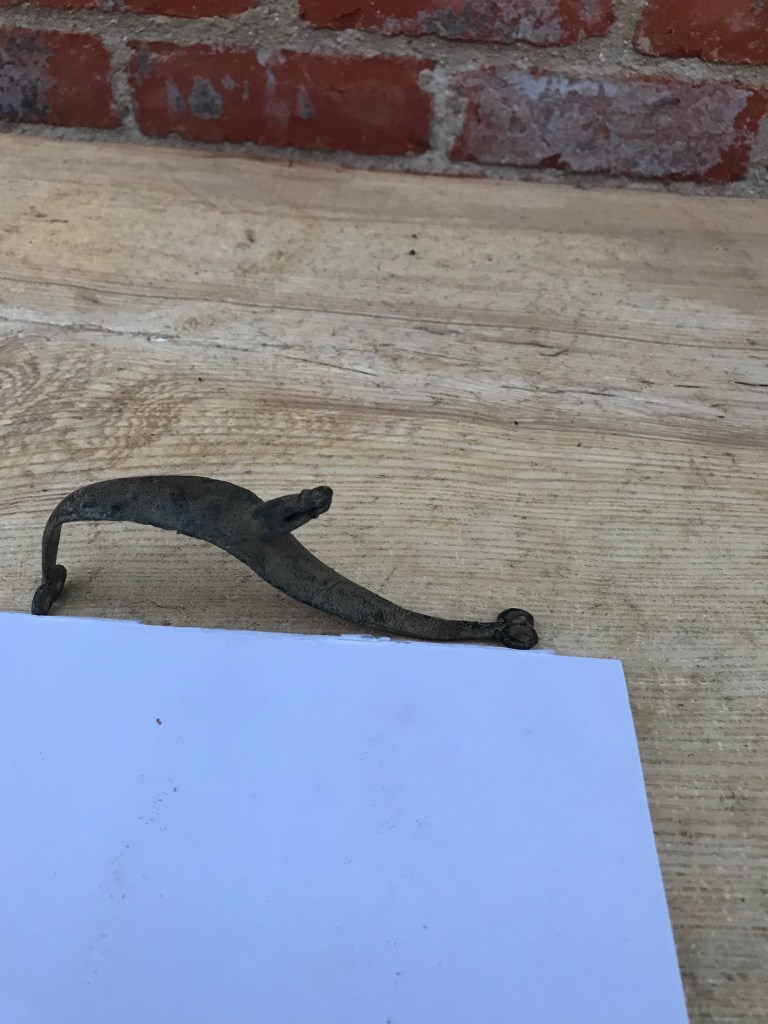

My father found an old spur in the fields around our farm” – Jennifer Wilson

As a child I used to play in the grounds of Hanby Hall and I found pieces of old muskets scattered everywhere” – Noel Riley

There’s nothing special about my [17th Century] house – it’s not like Oliver Cromwell ever slept here” – Philip Heyes

I have a copy of the John Claude Nattes painting of the planned reconstruction of Welton church in 1791” – Philippa Glanville

Come and see the moated site of Hanby Hall next to my house” – Andy Hill

My father found an old spur in the fields around our farm” – Jennifer Wilson

As a child I used to play in the grounds of Hanby Hall and I found pieces of old muskets scattered everywhere” – Noel Riley

Would you like to borrow this book of old photos of Alford?” – Julie Hardcastle

Poem – “Alford Fight”

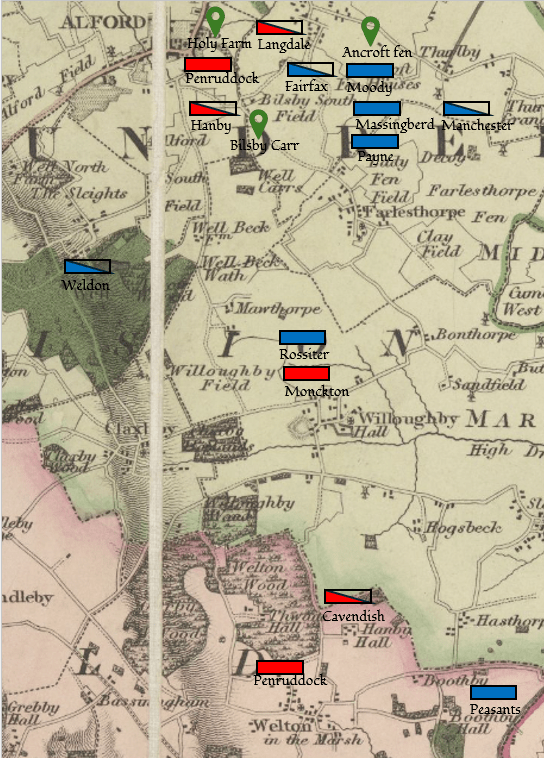

It turned out that Julie’s contribution was the key to connecting these tales and unlocking a shocking story of what happened in the village four hundred years earlier. The book of Alford photos contained a Victorian poem by Henry Winn that referred to a an English Civil War battle at Hanby Hall in 1643, covering the land and residents of Alford, Willoughby, Well Vale, Gunby, Scremby and Welton le Marsh. Controversy surrounds its authenticity as there is no current historical record (see below), however, research has shown evidence to support it. The origin of the Poem is discussed under the documentary evidence section.

Respected friend you ask from me A page of local history, Torn from the annals of that year Of sad events in Lincolnshire, When armed men mov'd up and down Our country lanes, from town to town; And party rage and hate were rife, Menacing property and life. When no man's chattles, house or lands Were safe from those marauding bands For loyal sword, and rebel pike, Were on the warpath much alike. Thank God! since sixteen forty three From Civil War we have been free. In those dark days of ruthless strife When neighbours sought each others life, If we may trust a gossip's tale There liv'd a Roundhead in Well Vale; Sir Lyon Weldon was his name, Enjoying more than local fame; For, to his party he was known A leading man in Alford Town; Where, sitting to enforce the laws, His heart espous'd the people's cause. He had a neighbour we are told, Whose seat between the Marsh and Wold Was known to bear its owner's name, And Hanby Hall they call'd the same. Sir William was a loyal knight, But late return'd from Riby fight; Where Cavendish, the wise and good, A troop of rebels had withstood And Hanby thought they could not fail To capture Weldon in the Vale; And curb the Marshmen, who, he said, Though full of brag, were half afraid. He press'd his chief to hurry down His vet'ran troop to Alford town; The road to Wainfleet then was plain, And Boston they might surely gain. The brave commander thought he might On such conditions risk a fight; So with his forces hurried down To Hanby Park, near Alford Town. His "right" and "left" extending far As "Holy Farm" from "Bilsby Carr". The volunteers the pastures fill Around the base of Hanby Hill, And Cavendish, to be in call, Fix't his headquarters at the Hall. The rebel party were not slow To meet in fight their daring foe; And muster'd up their troopers bold From the adjacent Marsh and Wold. The troop from Burgh, led by Payne, Pitch'd to the "left" in Bilsby lane; Moody from Scremby led his men To form the "right" by Ancroft Fen, And Massingberd of Ormsby tried To keep the "centre" well suppli'd. Thus stood the camp.

For four long days The country round was in a blaze; For troops were passing to and fro, Plundering alike both friend and foe; Each army willing to delay From different cause the bloody fray; Cavan with cares of state oppress'd, The rebel soldiers needing rest. At length came Fairfax with his band, And Manchester assum'd command; Cavan was summoned to his post, And thus dispos'd the royal host — The "right", or Marmaduke's brigade, Sir Philip Monkton's flag display'd; Penruddocks regiment was thrown Forward, to succour Alford town; Langdale's brigade mov'd to the front To start the fight or bear the brunt And so the bloody work began — The gallant Fairfax led the van. While Langdale's men sustain'd the fight, Moody, advancing from the right Cut through the line — horses and men In panic rush'd through Ancroft Fen, Where in the swamps the wounded fell; The rest before him fled pall-mell To Willoughby when came in sight Fresh foes advancing to the fight. Between two storms of deadly hail But few escap'd to tell the tale; These fugitives, too proud to yield, The peasants slew in Orby field. Fairfax and Cavan ever found Clever tacticians, kept their ground, Tho' many a brave and gallant knight Was wounded in the equal fight. Gardens and fields were trampl'd down, And damage done to Alford town. Penruddock, worsted in the field, Fled to the church, nor would he yield Till many corpses stain'd the floor, And cannon balls burst in the door. The captain, wounded in the strife, Ow'd to a Puritan his life; And Wilfrid's fane for many a day Bore marks of that exciting fray. Troops hurried up at wars alarms, From village workshops, halls, and farms, Are ever anxious to disband, Tho' incomplete the work in hand; And thus both armies melt away After the skirmish of the day But many a cottage home that night Was rob'd of all that made it bright. The mover in this local strife On his own manor lost his life, And e'er the hostile troops retire Hanby Old Hall was set on fire. Weldon escaped the trap 'tis said His wily neighbour for him laid. And thus abruptly ends a tale Of Hanby, Alford and Well Vale.

The course of the battle

From the Winn Poem and other documents (see the Documentary evidence section) it is possible to piece together the story of what happened in the battle. This can then be tested against the written and physical evidence.

- Hanby and Penruddock attack Weldon in Alford. Weldon holds them with a small force.

- Hanby and Penruddock form a line between Bilsby Carr and Ancroft Fen (presumably facing North towards Alford). Cavendish establishes headquarters at Hanby Hall to the rear (South).

- Parliamentarian Infantry reinforcements under Moody, Payne and Massingberd arrive from the North. (Although this appears inconsistent as Burgh and Scremby are to the South, but would make sense if they passed up the Willoughby road to Alford, bypassing the Royalists in the fields to their right, before engaging from the Alford-Bilsby road).

- Battle in the fields and marshes between Alford and Bilsby with parliamentarian reinforcements under Manchester, Moody and Payne.

- Several soldiers perish in the Bilsby marshes (unclear whether Royalist or Parliamentarian, although probably the former leading to their defeat).

- Royalist retreat to Willoughby, ambush by infantry under Rossiter, Monckton is captured

- Royalist retreat to their headquarters at Hanby Hall. Commander Sir William Hanby is killed, Cavendish escapes and Hanby Hall is burned down.

- Royalists leaving Hanby Hall attempt to reach Orby via the drive to Boothby Hall. There they are met by peasants from Welton le Marsh and are massacred.

- Royalist retreat to parish church (St Martin’s, Welton le Marsh). Puritan parliamentarians massacre everyone except commander, Colonel John Penruddock.

Documentary evidence

Poem “Alford Fight” by Henry Winn (1816-1914). [Winn]

The date of the poem is not known.

Henry Winn

The view against the poem

The poem appears in the book of old photos “Alford Town” by S.M.Crooke and P.E.Cromeby. this is accompanied by a rather disparaging text, arguing that the subject of the poem cannot be true:

This poem was re-published in 1965 by Mrs F. L. Baker, the grand-daughter of the poet, Henry Winn. Winn was a hard-working Victorian and lay preacher from Fulletby who lived to the age of 99. He wrote a large number and variety of poems, many of which are based on historical events in Lincolnshire. The `Alford Fight’, however, did not take place, and seems to have been the creation of a late-19th Century Alford curate, Rev Geo. Tyack, based on a Civil War skirmish near Alford, Scotland. Through-out the poem, Winn qualifies the story, so it seems even he was not convinced of its accuracy. The “respected friend” addressed in the first line is Mr Percy Tattershall of Toynton. `Hanby Hall’ was said to be an ancient farmhouse in the parish of Welton; it is now the name given to the large Georgian house which stands opposite St Wilfrid’s church.

The view for the poem

The suggestion that John Winn refers to Alford in Scotland (where there was an English Civil War battle in 1645) is clearly incorrect as many other local places around Alford in Lincolnshire are mentioned (Scremby, Burgh (le Marsh), Welton (le Marsh), Well Vale, Willoughby, Hanby, Wainfleet, Boston, Bilsby, Alford Holy Well, Ancroft Fen, Ormsby and Orby.

The reference to Hanby Hall “said to be” an ancient farmhouse in the Parish of Welton, did exist – you can read more at Hanby Hall.

However, Winn is confused about the identity of the Church, referring to it as “Wilfrid’s fane” meaning St Wilfrid’s church in Alford. However, as the Royalists were retreating southwards via Hanby Hall and Boothby Hall, the nearest church would have been St Martin’s in Welton le Marsh (1 mile), rather than Alford (6 miles) which was back towards Parliamentarian forces. As will be seen, physical evidence supports the identification of Welton le Marsh church.

BYGONE LINCOLNSHIRE, WORKS BY WILLIAM ANDREWS, F.R.H.S. published in 1891 [Andrews]

https://archive.org/stream/bygonelincolnshi02andruoft/bygonelincolnshi02andruoft_djvu.txt

ONE could scarcely find a country town whose aspect is more peaceful — an

enemy of the place, if it has one, might say more sleepy — than the little town of Alford. Its grey church tower looks down year after year upon its wide market-place and clean broad streets, and sees little change as time rolls on; and the rooks, cawing on their homeward way to the dark woods of Well, but seldom carry home tidings of any new encroachment by the habitations of men upon their ancestral ” hunting-grounds.” The very railway has been kept at a full arm’s length, and when recently a line of tramcars, with reckless daring, strove to desecrate the decorous streets of Alford with clang of bell and hiss of steam, a few short years sufficed to still the noisy emblem of progress, and to leave the highways once more in the dignified monotony of unbroken peace.

But in the turbulent days when King and Commons argued out their differences with crash of arms, Alford felt the shock of the constitutional earthquake, and showed herself no less able to bear her part than other more important places. Indeed, the condition of things in the little town was such at that time as to suggest that anything but peace reigned in the district, and that bickerings in the market and brawlings in the streets must then have been no infrequent sights and sounds. For in the centre of the town, under the very shadow of the church, lived Sir William Hanby, of Hanby Hall, a staunch adherent of Church and King, whose opinions, doubtless, were of no little weight with many of his poorer fellow-townsmen. But his rule was not undisputed, for in Well Vale dwelt Sir Lionel Weldon, who had thrown in his lot with the Puritans, and had his following also, no doubt, among his neighbours.

The turmoil of the town reached a crisis in June and July, 1645. On the morning of the 27th June, the Royalist leader, Cavendish, marched into the town with a strong force ; the movement was part of an attempt then being made by the King’s troops at Newark and Nottingham to force a passage to Boston, one of the Parliamentary strongholds ; but a minor motive is said to have been the hope of capturing the said Sir Lionel Weldon, a hope in which they had been specially encouraged by Sir William Hanby.

Hanby Hall was made the Royalist headquarters, and the troops lay encamped on the south side of the town, one wing at Bilsby, the other at Holy Well Farm. The low ground round the latter position was at that time but ill-drained, and the marsh proved fatal to many in the subsequent attempt to retreat.

Every effort to seize the person of Sir Lionel proved ineffectual, and the Parliamentary forces, hastily gathered under Sir Drawer Massingberd, though too feeble to attempt an attack, succeeded in keeping the Royalists in check until further help arrived. Late in the day, on July 1st, the Earl of Manchester came up with a considerable force of Parliamentarians, and encamped in Bilsby Field, while news was brought that cavalry and artillery were advancing from Burgh to aid the same cause. No movement was made that day, the Puritan troops being wearied with forced marches, and the Royalist leader being temporarily absent.

On the following day, July 2nd, however, the fight began betimes ; the right wing of the Royal army was vigorously assailed by the troopers of Moody of Scremby, and Payne of Burgh, and completely routed ; numbers perished in the swamp, and the scattered remnant was met at Willoughby by Rossiter, advancing from Burgh, and practically annihilated. The battle was not so easily won in the rest of the field, but at last the whole position was carried by the Earl of Manchester’s forces, the Royalists being scattered with great slaughter.

Cavendish got safely away, but Sir William Hanby was among the slain, and his Hall was partially destroyed. The fragment of a regiment serving under Colonel Penruddock took refuge in the parish church, and here, as in so many other instances, the Puritans sullied their victory by the exhibition of their barbarity ; not only did the sacred walls prove no City of Refuge for the vanquished, but the completed victory was signalised by the destruction of almost everything which they contained. Of this desecration, a relic is still to be seen : the tracery of the north and south windows of the Sacrarium of the church is filled with some fragments of old glass, that by their richness of tone put to shame the modern glass beside them, and more than that, prove to us how beautiful must have been “the dim religious light ” within those walls before the passions of men brought the hot breath of war upon the place, to blight the beauty both of men and things.

Lincolnshire notes and queries [Bateman]

This third source relates the story in an extremely disparaging way, however, parts of their own case are obviously incorrect, denying the existence of Hanby Hall near Alford.

DEVOTED TO THE ANTIQUITIES, PAROCHIAL RECORDS, FAMILY HISTORY, FOLK-LORE, QUAINT CUSTOMS, &c., OF THE COUNTY. EDITED BY The REV. CANON MADDISON, M.A., Vicar’s Court, Lincoln ; The REV. W. O. MASSINGBERD, M.A., Ormsby Rectory, Alford j AND E. MANSEL SYMPSON, M.A., M.D., Deloraine Court, Lincoln. VOL. IX. January i, 1906, to October I, 1907. Horncasstle : W. K. MORTON & SONS, Ltd.

The Battle of Alford. — The Battle of Alford is an interesting example of a spurious tradition obtaining a wide currency ; it has appeared in all the authority of print ; and a local guide book gives it as an historical fact relating to the town. What, then, is the origin of the myth ?

Some forty or fifty years ago there flourished, more or less, in Alford, a person named Wm. Maldon Bateman, known locally as the Alford poet. This man, for his own amusement we will hope, or for purposes of deception, wrote “A short account of the battle fought at Alford, 2 July, 1645, between the Royalists under Cavendish, and the Parliamentarians under Montague.”

On Bateman’s death the MS., bound up with a volume of a local magazine, came into the possession of Mr. B. Hibbitt, of the White Horse Hotel. Here it became an object of interest to his numerous customers, who, receiving the story with a large and simple faith, were the means of spreading it widely abroad throughout the neighbourhood. When Mr. Hibbitt died the book disappears and is forgotten, but the tradition, like John Brown’s soul, goes marching on. No exposure would now be likely to kill it, but for the sake of the future historian of Alford, it may be well to place the truth on record.

Mr. Bateman’s narrative is briefly as follows -“The King’s forces under Cavendish came down upon Alford “ with a fell swoop,” their object being to seize Sir Lionel Weldon, and to “force a route to Boston.” The plan of seizing Sir Lionel was “instigated by Sir Wm. Hanby, of Hanby Hall, Alford.” The Royalists took up a position in Hanby Park, their left resting on Bilsby Carrs, their right on Holy Well Farm, protected by swamps in their rear, and a wood, “of which a fragment yet remains.”

Sir Drainer Massingberd, of S. Ormsby, tried to hold them in check. The Parliamentary Army, under the Earl of Manchester, then came up and took ground in Bilsby Field, its left strongly protedted by swamps, and its right by Ancroft Fen. Then ensued a desperate battle, in which the Royalists were duly defeated and driven towards Willoughby, where they were met by Colonel Rossiter, “with his regiment of infantry.” “ After a conflict of very short endurance the ill-fated fugitives were cut to pieces. A small party of them nearly reached Orby, but were slain to a man in the road that now forms the avenue of Boothby Hall by the enraged peasantry.” Colonel Penruddock, who was with the Royalists, with the remnant of his regiment, took refuge in the church. There, they were “ mercilessly slaughtered,” only the Colonel, who was severely wounded, escaping.

We might reasonably suppose that where there is so much smoke there must be some fire, and, indeed, we find that the whole story is founded on two facts. A battle was fought at Alford on July 2nd, 1645 — but at Alford, in Scotland, between Montrose and the Covenanters under General Baillie, when the latter was defeated. Colonel Rossiter did defeat the Royalists at Willoughby — but at Willoughby, near Nottingham, on July 4th, 1648, and under the command of Sir Philip Monkton. For the rest — Cavendish was slain in a skirmish near Gainsborough, on July 28th, 1643. Penruddock was a west country man, and probably never set foot in Lincolnshire.There is not, and never has been, a house in Alford called Hanby Hall.

The position of the armies and the various events of the fight are a patchwork gathered from the different battles of the war. The defence of the church is taken from the real exploit of a Lincolnshire man, Colonel John Bolle, who, finding himself surrounded by the enemy, retired into the Church of Alton, near Winchester. “After a short resistance,” says Clarendon, “ in which many were killed, the soldiers, overpowered, threw down their arms and asked quarter, which was likewise offered to the Colonel, who refused it, and valiantly defended himself, till, with the death of two or three of the assailants, he was killed in the place, his enemies giving a testimony of great courage and resolution.

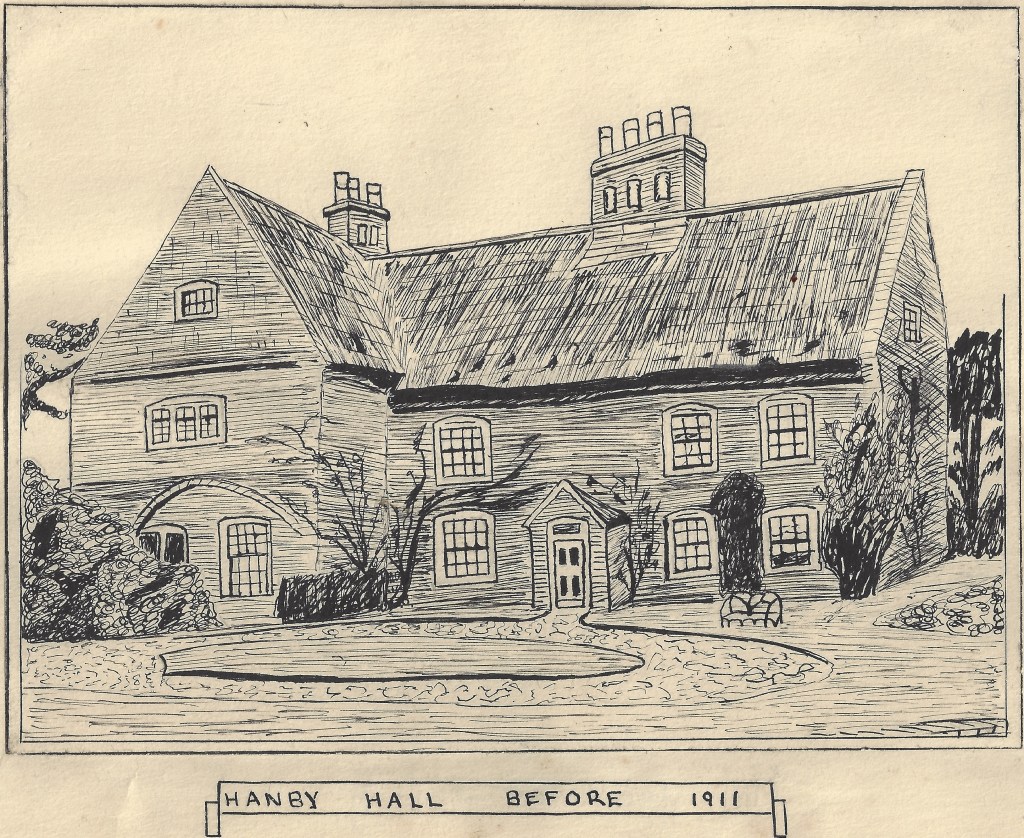

Notes discrediting the commentary on the Bateman account

The dismissal of the existence of Hanby hall shows an unbelievable disconnection with the facts and local tradition, thereby discrediting the rejection of the rest of the story. At the time it was written (1907) there was a significant Georgian (1730, so post Civil War) building in Alford called Hanby Hall (built in the Eighteenth Century by John Andrews). Furthermore, the original Hanby Hall (Rebuilt late 17th century on the site of the medieval manor house) on Hanby Lane leading South from Alford was still occupied and remained until 1975. Clearly this author was not from Alford and did not trouble themselves to check their basic facts with local residents.

It is interesting to note that Bateman entitles his account “A short account of the battle fought at Alford, 2 July, 1645, between the Royalists under Cavendish, and the Parliamentarians under Montague”. Is “Montague” a corruption of “Manchester” deriving from multiple generations of orally passed accounts of the battle?

Cromwell letter

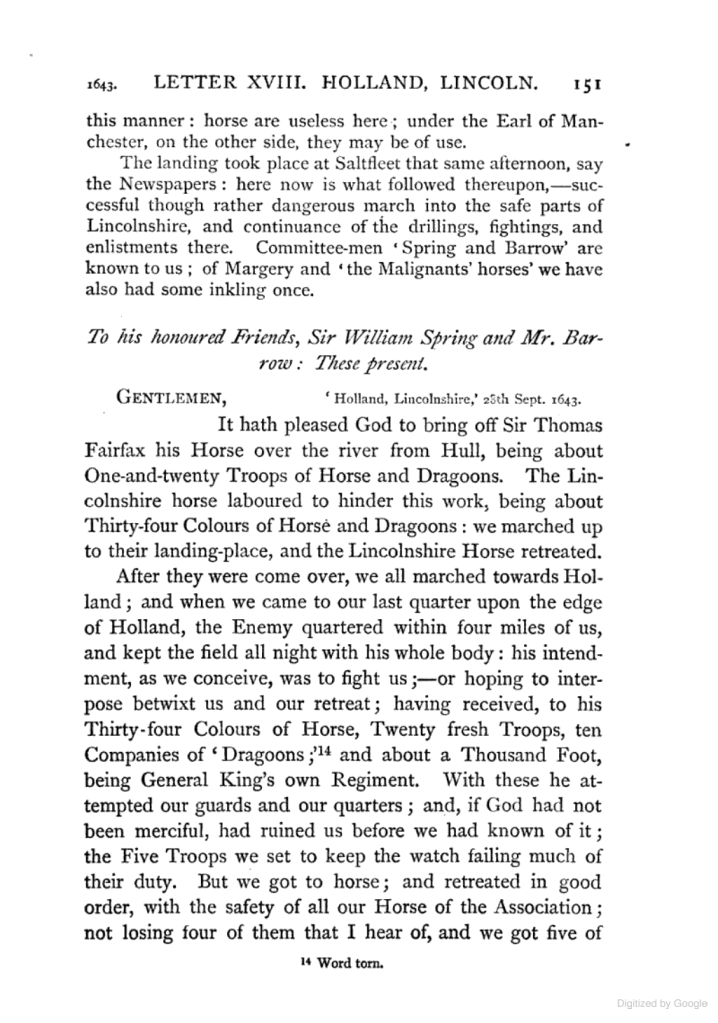

Dr. Jonathan Fitzgibbons, Senior Lecturer in Early Modern History at the University of Lincoln, reports a letter from Oliver Cromwell dated 28 Sept. 1643. “Cromwell mentions that just as his forces were on the edge of Holland they were ambushed by Henderson’s larger force of Royalists from Newark – they managed to get away to Boston losing only a few men, but it’s not clear where exactly this encounter happened”.

This supported by other references:

[Fairfax and Cromwell] had some difficulty in eluding a force of 5000 Cavaliers, who endeavoured to intercept them. At Louth, where Cromwell is said to have slept on the 27th [September 1643], he would be joined by the contingent from Barton. Memorials of Old Lincolnshire, chapter by Rev E H R Tatham (1911)

…Their landing [in Barton from Hull after 16th September 1643] was covered by Cromwell’s cavalry; despite the attentions of a large body of Royalist Horse… Seventeenth Century Lincolnshire by Professor Clive Holmes (1974)

Observations from the letter

Dr Fitzgibbons kindly provided the reference to Cromwell’s letters of 26th and 28th September 1643, reproduced below from the book “Oliver Cromwell’s letters and speeches” by Thomas Carlyle, 1871. There are a number of details in the text that support the three antiquarian accounts fo the battle of Alford, Hanby and Welton le Marsh. It should be considered that other researchers may not have considered this possible location for the events, unless they were specifically looking for those clues, which are subtle, as can be seen:

- Fairfax lands at Saltfleet on 26th September 1643 and Cromwell deters a force of Royalist cavalry. This demonstrates that Cromwell and Fairfax were approaching Holland in Lincolnshire (see notes below) towards its Northern boundary.

- Cromwell states “we all marched towards Holland“. This is the old “Part of Holland” (ridings or division of Lincolnshire. See 1870-72, John Marius Wilson’s Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales). (The other parts being Lindsey and Kesteven). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parts_of_Lincolnshire

- Cromwell refers to the engagement at “The edge of Holland“. The Wapentake of Candleshoe is the Northern border of which contains Welton le Marsh, the site of the reported Church siege.

- One common objection from readers of the story of the battle of Alford, Hanby and Welton is the list of significant characters in the English Civil War being referred to in the antiquarian accounts. A footnote by Carlyle under the letter suggests that the Earl of Manchester (overall commander of Parliamentarian forces in the East of England) joined Cromwell and Fairfax at the time (29th September 1643) of the battle referred to in the letter, although the language is somewhat contorted. “The Earl of Manchester, recaptor of Lynn Regis lately, is still besieging and retaking certain minor strengths and Fen garrisons,—sweeping the intrusive Royalists out of those Southern Towns of Lincolnshire. This once done, his Foot once joined to Cromwell’s and Fairfax’s Horse, something may be expected in the Midland parts too.”

- After a long discussion on the morals of commandeering horses from local civilians, to provide for his troops, in his letter of 28th September 1643 Cromwell states “A horse was sent to me, which was seized out of the hands of one Mr Goldsmith of Wilby.” Wilby must surely be a phonetic equivalent of the village of Willoughby in the middle of the battle area, halfway between Alford and Welton le Marsh. Willoughby is mentioned in all three antiquarian accounts.

Memorials of Old Lincolnshire [Sympson]

http://www.public-library.uk/dailyebook/Memorials%20of%20old%20Lincolnshire.pdf

Whilst not referring directly to Alford, Hanby or Welton le Marsh, this book does cite Cromwell and Fairfax “Eluding a force of 5000 cavaliers” near Louth on 26th September 1643. This is probably the same event recorded in Cromwell’s letter of 28th September, referenced above. It should be noted that this was a significant force, double the size of the whole Royalist army at the battle of Winceby. https://www.historyofwar.org/articles/battles_winceby.html

News had come from Hull that the cavalry of Sir Thomas Fairfax was useless within the walls, and that their horses were dying from the brackish water. It was determined to bring this body of twenty-one troops across the Humber into Lincolnshire ; and Cromwell, with Lord Willoughby, executed a daring march through the Wolds, then infested with Newarkers, to Barton, whither some of the cavalry were transported on September 18th. But it seems to have been thought inadvisable to bring across the whole body in full view of the besieging army. On the 23rd both commanders were in Hull, bringing powder and provision for the garrison ; and on the 26th the greater part of the cavalry were put on shipboard and landed, apparently the same evening, at Saltfleet Haven. At this old-world seaport there still stands a manor-house, then the property of Lord Lindsey, but somehow—by sequestration or otherwise—at the disposal of his kinsman of Parham, where Cromwell and Fairfax passed the night with their host. It is full of ancient furniture, and “Cromwell’s bed ” is still pointed out to the credulous.

With the dawn the troops were on the move, and had some difficulty in eluding a force of 5000 Cavaliers, who endeavoured to intercept them. At Louth, where Cromwell is said to have slept on the 27th, he would be joined by the contingent from Barton ; and here, perhaps, a few troops were detached with Fairfax for scouting purposes round Horncastle. On the 28th Cromwell was in Boston, weeping ” that there was no money for his soldiers, and pushed on to Lynn to hasten the advance of Manchester and his infantry.”

Our Village by Arthur Hundleby [Hundleby]

A most remarkable local history book, “Our Village” is the story of Welton le Marsh written by Arthur Hundleby while he was still at school in 1938. It is beautifully and written and illustrated, bringing together recollections of villagers and subject matter experts.

Hundleby provides information on the destruction of Welton church:

Our church is not a very ancient building, as it was entirely rebuilt in 1792 and the years following. The original building was built of local white stone, evidence of which is to be found at the bottom of the walls of the present structure.

This earlier church, of which very few remains now exist, came to an untimely end on April 9th, 1791. On the flyleaf of one of the church registers is written “Welton Church steeple fell down, Saturday, April 9th 1791 about 7 o’clock in the morning.” This entry is the only mention to be found of what must have been a great calamity to the church-going section of the community, a very considerable proportion of the population.

Almost immediately a scheme for rebuilding the almost entirely demolished church was started and we hear from old inhabitants of the village, how their grandfathers spoke of almost insuperable difficulties encountered in attempts to raise the money.”

Note that Hundleby refers to “the almost entirely demolished church”. This could be either because the spire had fallen on the nave, or that the church was already damaged and the the spire was the last part standing, becoming the impetus for the villagers to get started with the rebuilding. If the latter was the case, it supports the story of the church being destroyed during the English Civil War siege.

Church building restoration expert Trevor Oliver suggests that the arch leading to the sanctuary is of Saxon origin (albeit support by a more modern wooden beam, whose installation is remembered by villager Bob Sharpe when his boss did the work in 1978). This would suggest that whatever the cause of the collapse of the nave, that part survived and older stonework may be hidden by the current Georgian brick skin around it.

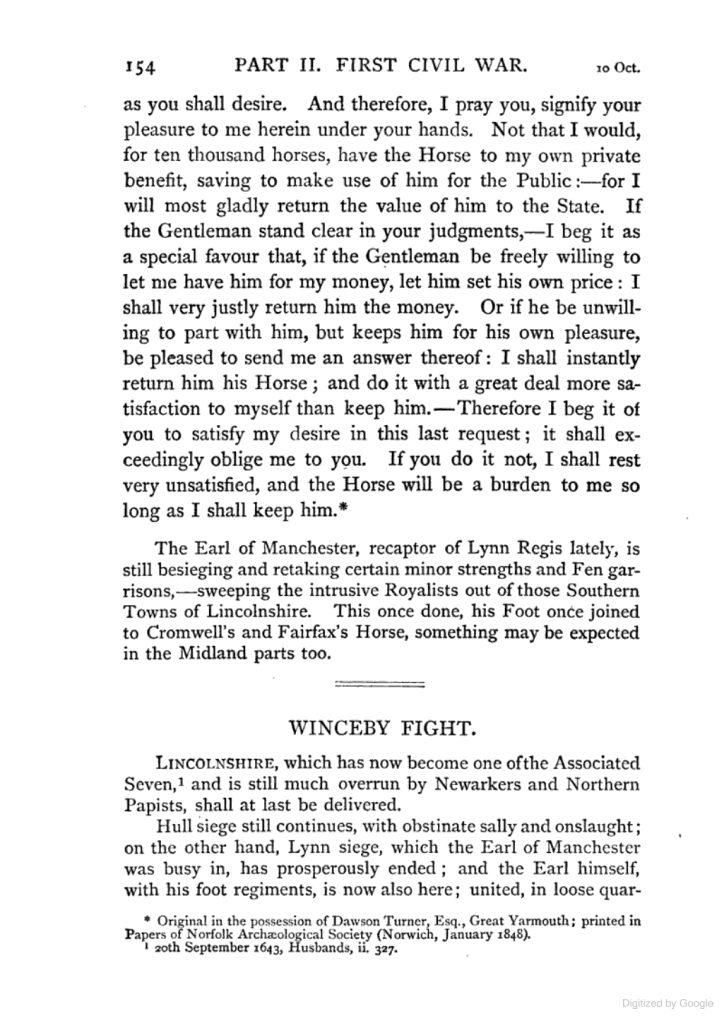

Painting of the proposed reconstruction of Welton le Marsh church by Jean Claude Nattes, 1791. Commissioned by Sir Joseph Banks.

Fortuitously, at the time of the church spire collapse, the eminent Lincolnshire naturalist Sir Joseph Banks commissioned the artist Jean Claude Nattes to paint pictures of significant buildings in the county. This included Welton le Marsh church. Interestingly there are a few differences between the picture and the physical church (at least as it appears today);

- No house was ever built behind the church (Pictured adjacent to the bridge over Welton beck)

- When it was rebuilt in 1792, it had fairly ugly round topped windows (see illustration below), which were replaced during the Victorian restoration of 1898 with Gothic pointed arch windows, thus finally achieving the appearance shown in the painting.

- There are windows on the South side of the second floor of the tower, not shown in the painting.

It would seem likely that the painting was created from an architect’s drawing, rather than from an actual view of the church.

Illustration of St Martin’s church as it appeared before 1898 restoration, drawn by Arthur Hundleby in 1938

Differences between sources

Note that the Bateman account and the Lincolnshire Notes sources represent two different perspectives for and against (albeit presented within the same document).

Whilst the John Winn poem and the William Andrews book and the William Maldon Bateman account are very similar in their stories, their are some differences in the details. This would suggest that they are not copied one from the other, but share a common (and distant) source, with errors introduced through oral and written transcriptions.

John Winn sets the date to be 1643 (the same as the nearby battle of Winceby) whilst William Andrews seem to be confused with the Battle of Alford in Scotland during the Scottish Civil War on 2nd July 1645.

The name of the Parliamentary commander is documented as “Sir Lyon Weldon” by Winn, and “Sir Lionel Weldon” by Andrews. Presumably corruption by an oral account.

The Language between the Bateman account and Andrews work is quite different in character suggesting there is no direct copying link, but again a common source.

Another interesting difference in perspective is that at the end of the Andrews work, he discusses the coloured panes of glass in Welton church (proving that he had visited the place), thereby may have had local perspectives on the historic events, whilst the commentary on the Bateman account denies the existence of Hanby Hall near Alford (which would have been occupied at the time), shows the lack of contact with local knowledge.

Analysis of the story

To provide context, the map below shows the sites of major battles and the movement of key figures in Lincolnshire during 1643.

Participants in the battle – Parliamentarians

A potential criticisms that might be laid against the story includes the names of many of the significant figures of English Civil War history – what would they be doing in Welton le Marsh in 1643? The answer is straightforward in that they were present at the Battle of Winceby, just 11 miles away.

Manchester

Edward Montagu, 2nd Earl of Manchester, KG, KB, FRS (1602 – 5 May 1671) was an important commander of Parliamentary forces in the First English Civil War, and for a time Oliver Cromwell’s superior.

Prior to the battle of Winceby, he left the siege of King’s Lynn for Horncastle on 16th September 1643. On 7th October 1643 Manchester marched from Boston to Horncastle. On 11th October 1643, he took part of his force and arrayed them on Kirkby Hill (11 miles from Welton le Marsh) to prevent the Bolingbroke garrison from leaving the castle and organizing an attack from the rear.

Fairfax

Sir Thomas Fairfax (17 January 1612 – 12 November 1671) was an English army officer and politician who commanded the New Model Army from 1645 to 1650 during the English Civil War. On 18 September 1643, part of the cavalry in Hull was ferried over to Barton, and the rest under Sir Thomas Fairfax went by sea to Saltfleet on 16th September. Wiuth Cromwell, he encountered a force of 5000 cavaliers near Louth. A few days later, the whole joining Cromwell near Spilsby. Following this route would have taken him through Alford, Willoughby and Welton le Marsh.

Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 1599 – 3 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician, and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history.

Although Cromwell is not mentioned in any of the three written accounts of the battle, he was historically little known ahead of his action at the Battle of Winceby on 11th October 1643, therefore, there would be no reason for contemporary chroniclers to mention him. Cromwell was garrisoned “near Spilsby” before Winceby, less than 6 miles from Welton le Marsh. The reference allows that he may have been even closer and therefore possibly involved in the battle.

He travelled from Boston, reaching Barton-upon-Humber on 18th September 1643 to support the arrival of troops being ferried from the siege of Hull. He met Fairfax in Louth and together they encountered a force of 5000 royalists on 26th September. He rejoined Fairfax in Spilsby and travelled on to Boston on 28th September.

Rossiter

Colonel Sir Edward Rossiter (1 January 1618 – 9 January 1669) was an English landowner, soldier and politician from Lincolnshire. He fought with the Parliamentarian army in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, and sat as an MP at various times between 1646 and 1660.

He captured Sir Thomas Monckton at the battle of Willoughby Field (which modern sources place at Willoughby in Nottinghamshire rather than Willoughby in Lincolnshire).

On September 3rd 1643, The Earl of Manchester’s Parliamentarian army marched to the Thames valley. The defence of Lincolnshire was left to Rainsborrow and Col Sir Edward Rossiter’s regiment. On October 29th The Parliamentarians led by Col Sir Edward Rossiter, surprised and defeated a 2,000 strong Royalist relief force, heading for Crowland. Therefore Rossiter was in the area of Eastern Lincolnshire at the time of the battle of Winceby.

Massingberd

Between 1640 and 1660, Sir Drayner began construction of the former manor which later became South Ormsby Hall. Sir Drayner and his brother, Sir Henry Massingberd both fought in the English Civil War as parliamentarians against King Charles I, but they were pardoned for their part in the revolution after the restoration of the monarchy.

Participants in the battle – Royalists

There were four royalist commanders with the name Cavendish; which one is being referred to in the accounts of the battle of Welton le Marsh? Charles Cavendish is the obvious candidate, but he was killed in July 1643 before the events around the battle of Winceby, where other protagonists were present.

Cavendish

Second son of William Cavendish, 2nd Earl of Devonshire. Royalist Colonel-general commander-in-chief Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire, died at the battle of Gainsborough 28th July 1643 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Cavendish_(general,_died_1643)

Cavendish fought at Louth (16 miles from Welton le Marsh) in June 1643.

Cavendish’s death in the middle of 1643 casts doubt that the action was part of the build up to the battle of Winceby in October, which document the presence of notable figures (Manchester, Fairfax) in the Welton area. However, the fact that all three written accounts of the battle of Welton include Cavendish may suggest that the events happened earlier in the year, or it was a different Cavendish as noted above.

Monckton

In 1642 Sir Philip Monckton volunteered to fight on the Royalist side and became a captain under Sir Thomas Metham. Monckton served at the seige of Hull in 1642.

He was captured by Colonel Rossiter at the battle of Willoughby field. Modern sources cite the battle of Willoughby as being in Nottinghamshire, however, Sir Philip’s own words refer to moving his troops into Lincolnshire for this engagement. Historians may have confused events. Sir Philip himself also appears confused in a number of his own entries with names of places that do not exist (or he had corrupted). The fact that all three sources (Winn, Bateman, Andrews) mention either Monckton and / or Colonel Rossiter (Monckton’s nemesis, by whom he was captured at Willoughby) seems like a great coincidence, although it is possible that all three confused events.

It is interesting to note that a map of 1855 describes the area between Alford and Willoughby as “Willoughby Field”, a name that has since fallen out of use and therefore has not been apparent to researchers.

Sir William Hanby

The name of Sir William Hanby does not appear in modern documentation. This is most probably as he died at the battle as described in the documentary sources and had no surviving descendants. It should be noted that:

- A new Baronetcy of Hamby (Hanby) in Lincolnshire was created for Sir John Buck by the restored King Charles II in 1660. Buck baronets. This suggests there were no living claimants to the Hanby estate. (Although there were members of the wider Hanby family living in Hanby and Alford until at least 1730 when Richard Hanby built the Georgian Hanby Hall in Alford).

- The Hanby family of Hanby Hall in Lincolnshire were recorded before the civil war. The last recorded reference was to the sale of “Hambye House” in 1636 and to “Edward Hamby of Alford” who is listed as buying property in 1593. https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/16940862/alford-manor-house-alford-lincolnshire-archaeology-data-service

- John Hanby (possible relative, connection to Hanby Hall not proven), emigrated to Virginia, America in 1642. https://www.houseofnames.com/uk/hanby-family-crest

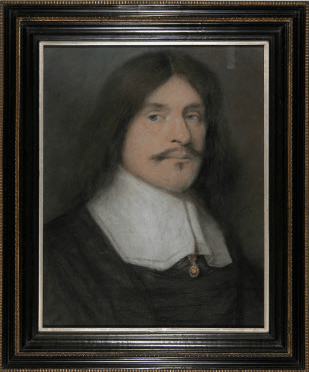

Colonel John Penruddock

Colonel John Penruddock, commander of the regiment besieged in Welton le Marsh Church.

Colonel John Penruddock was the commander of the last surviving regiment of royalists that took shelter in Welton le Marsh Church. He survived the siege by being spared by a puritan, but was beheaded in 1648. (as attributed on the above painting of him. Note the text of the website displaying the picture wrongly connects this to his son, the handwritten note on the reverse states that he was executed in the reign of Charles I (who was in turn executed in 1649). His son, also Colonel John Penruddock, was later executed in 1655 for a rebellion against Oliver Cromwell.

Langdale

Marmaduke Langdale, 1st Baron Langdale (c. 1598 – 5 August 1661) was an English landowner and soldier who fought with the Royalists during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

No references have been found placing Langdale near Winceby, but he is noted at the siege of Hull beforehand.

Consistency of references to participants in the battle

The table below shows the three primary documentary sources (Winn, Andrews, Bateman) have a good degree of mutual consistency in the names that they cite, albeit with some differences which support the possibility that they come from a common historical event but via different oral routes over two hundred years. Note that none mention Oliver Cromwell, however, this is not surprising as before the battle of Winceby where he made his name, he would not have been sufficiently notable to contemporary chroniclers.

| Protagonist | Alliance | Winn | Andrews | Bateman |

| Manchester | Parliament | Y | Y | Y |

| Weldon | Parliament | Y | Y | Y |

| Fairfax | Parliament | Y | ||

| Rossiter | Parliament | Y | Y | |

| Massingberd | Parliament | Y | Y | Y |

| Cromwell | Parliament | |||

| Cavendish | King | Y | Y | Y |

| Monckton | King | Y | ||

| Hanby | King | Y | Y | Y |

| Langdale | King | Y | ||

| Penruddock | King | Y | Y | Y |

Physical evidence

Musket furniture

When he was a child, Noel Riley, (who had been evacuated from Grimsby to Welton le Marsh in 1940 and spent the rest of his life in the village) played in the grounds of the derelict Hanby Hall. Noel discovered several pieces of muskets spread across the garden. If they had been from a gun rack, then they would have been in a single place. The fact that they were widely scattered suggests they were involved in some sort of fight. Throughout his life, Noel remained convinced he had found evidence of a significant historical event. Sadly, it was only after he passed away in 2024 that the evidence was amassed to prove that he was correct.

English Civil war Muskets showing the type of metal furniture found by Noel Riley

Musket ball finds

Willoughby village hall (between Alford and Hanby Hall) has a metal detecting finds display, which includes large numbers of musket balls, which suggest a military engagement happened in the area.

Spur

Jennifer Wilson’s father found a seventeenth century spur at their farm (quite possibly lost by a cavalryman during the battle), just to the north of the church, at the end of Beck Lane.

This appears to be a seventeenth century military style of spur, as used in the English Civil War. For comparison, a more ornate version can be seen among the siege exhibits of Goodrich Castle https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/goodrich-castle/history-and-stories/life-under-siege/

Musket ball marks

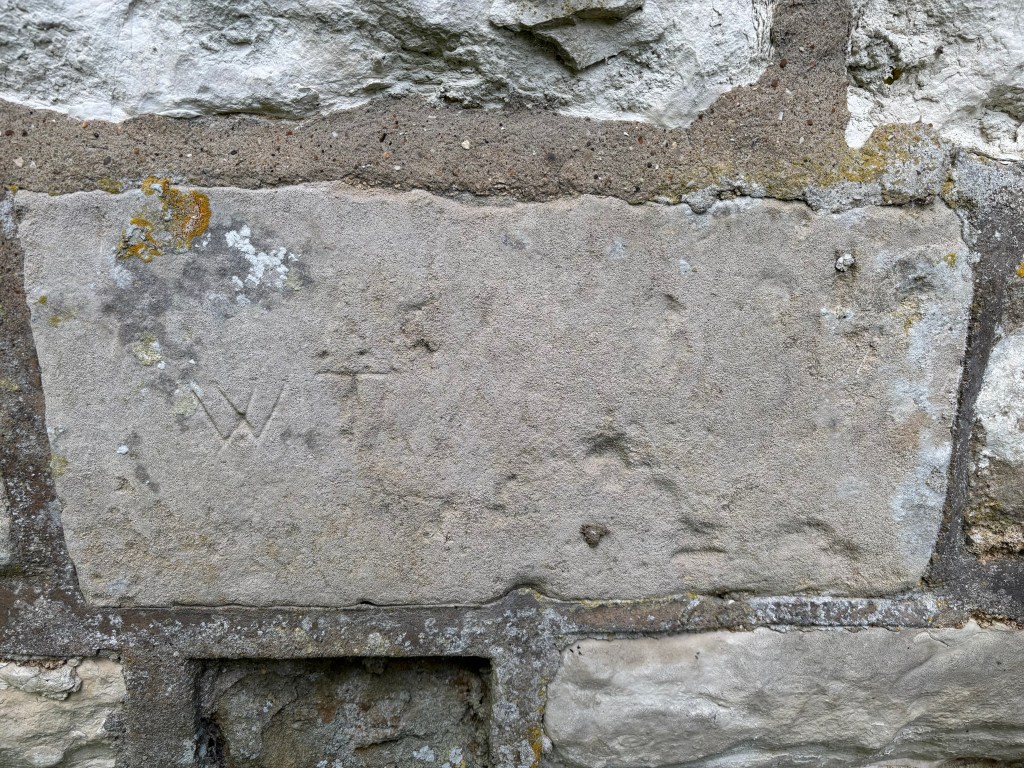

If the siege of the church had happened as described in the documented accounts, then there should be evidence of musket and cannon ball damage to the walls. However, it would also be expected that when the stone blocks were re-used in the construction, any damage would be placed facing the inside of the church where it could be plastered over. Fortunately, more than twenty stones show musket ball and grapeshot marks on the walls of Welton le Marsh church.

Fact check – are these musket ball marks?

As a means of comparison, the following pictures are of Old Bolingbroke Church which was known to be heavily damaged by Royalists whilst Bolingbroke Castle was under siege from Parliamentary forces. It can be seen that whilst many musket and cannon marks have been repaired with mortar, the exposed marks are similar to those on Welton le Marsh Church.

Evidence of rebuilding of mediaeval walls of Welton Church

Stones with engravings that would have been inside the church when made, are now on the outside. This demonstrates that the mediaeval blocks have not remained in their original arrangements but have been re-laid. It is presumed that damaged stones would have been turned to face the side, where they could be covered by plaster. It is, therefore, surprising that any damage can be seen at all. It is highly likely then that many more stones with severe battle damage are hidden under plaster inside the church, which may revealed by future restoration work.

Hanby Hall

Postcard of Hanby Hall (showing the original mediaeval name “Hamby”), Welton le Marsh

The idea suggested in the commentary on the Bateman story that “There is not, and never has been, a house in Alford called Hanby Hall.” is contested by many villagers of Welton le Marsh that visited the site before it was demolished in 1975, undermining the validity of the criticisms from people that clearly did not know the area or local customs.

From the architecture it is apparent that pictured Hanby Hall was built after the middle of the Seventeenth Century, exactly as would be expected if the medieval building had been burned down during the English Civil War.

Drawing of Hanby Hall showing original Hanby Hall with thatched roof by Arthur Hundleby (published 1938)

Proof of hypothesis

Thwaite Hall

The hypothesis is:

- The three Victorian accounts of the battle in Alford, Hanby and Welton le Marsh are true.

- Royalist troops were besieged in Welton le Marsh church, resulting in its destruction in 1643.

- Some of the stone blocks from the remains of the church were used to build Thwaite Hall in 1739.

- When the Welton le Marsh church was rebuilt in 1792, there were not enough stone blocks remaining (as they had been used for Thwaite Hall) so the remainder was constructed in brick.

If all of this is correct, the theory can be tested by examining Thwaite Hall – we would expect to see Musket ball marks in its walls – which is exactly what is seen:

Pictures of musket ball holes on the inside and outside walls of Thwaite Hall, Welton le Marsh.

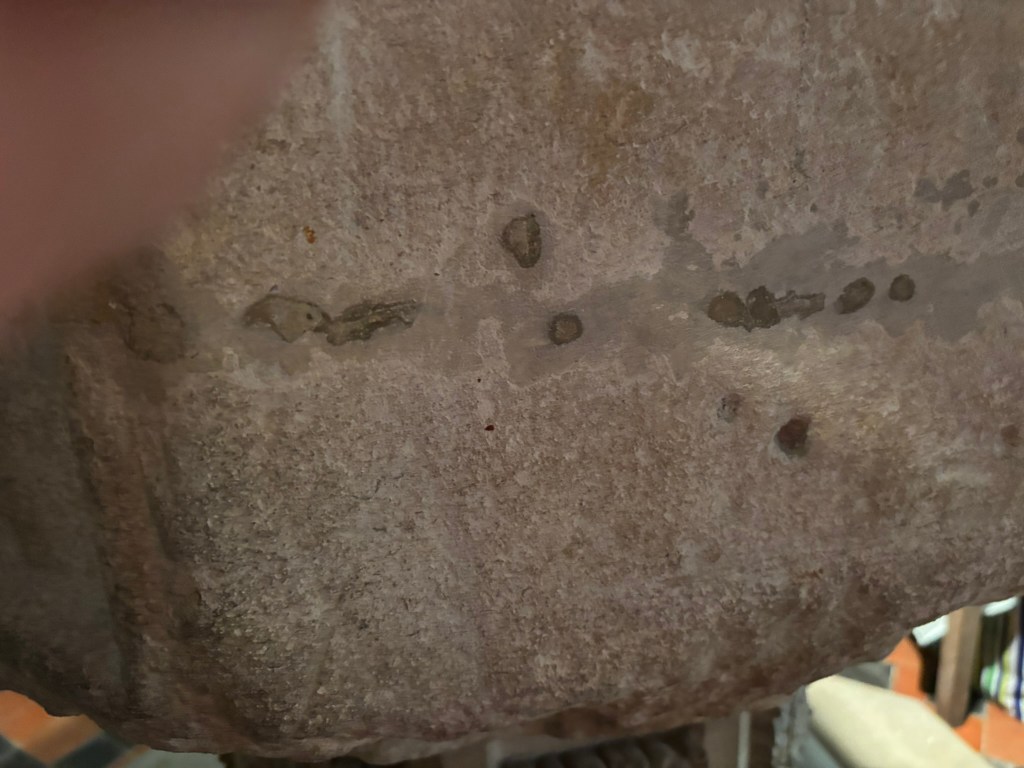

Welton Church Font

Arthur Hundleby records the story of the mediaeval church font:

Then, twenty years later (1912) [after the restoration of the church in 1898], a very interesting discovery was made. An old cattle-trough was noticed in a field near the church. Unlike most cattle troughs this one was round and apparently sunk some little distance into the ground. Further-more, queer markings were observed on its side and closer examination revealed the presence of a comparatively well preserved font dating to the fourteenth century.

Apparently it must have been taken from the debris of the wrecked church in 1791. It was ultimately secured for the church in 1914 and after repair and careful restoration was once more placed in its rightful position. Mr Gamble F.R.I.B.A. supervised the work and also designed a pedestal and base for it.”

Why was the medieval church font found in a field near the church? Hundleby suggests it may have been removed in 1791, however, if it was laying in the ruins of the church for a few months in 1791 between the spire collapse and the beginning of the rebuilding, it is unlikely anyone would have contemplated removing such a sacred object for agricultural purposes. Alternatively, if it had been laying in the rubble for over a hundred years after 1643, with no obvious prospect of reconstruction and other villagers were plundering material (including to build Thwaite Hall in 1739), then it would seem quite reasonable to take and re-purpose it.

Musket ball marks on the font

If the font had been present in the medieval church at the time of the siege in 1643, then it might be expected to show signs of battle damage, particularly as the parliamentarians apparently used a cannon to break down the church doors and it would have been the only hard cover within the church (wooden pews would not have stopped musket balls).

An inspection shows multiple musket ball marks.

Battle damage marks on the church font

Challenges to the story

A number of questions have been raised with views opposing the story set out above.

Alford church

The Henry Winn poem refers to St Wilfrid’s church in Alford – so perhaps the siege happened there rather than St Martin’s church in Welton le Marsh.

Alex Peters made a visit to Alford Church in the summer of 2025, seeking to find evidence of battle damage similar to that seen at Welton le Marsh and Old Bolingbroke churches. Whilst there were many examples of water erosion on the stone work, indicating it had not been repaired or replaced in a long time, no musket ball or similar marks were seen. It is possible that some may be there, unnoticed, as the battle began in Alford, however there is certainly no support for the violent siege described in the written accounts.

Hanby family

Online sources (primarily genealogical sites) do not have any reference to the Hanby family after the 16th Century.

Following the church visit, Alex Peters crossed the road to the Georgian building named “Hanby Hall” in Alford https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hanby_Hall. Noticing an elderly couple working in the garden, he confirmed that they were the owners and enquired into their knowledge of the history of the building. They confirmed that Richard Hanby came from Hanby Farm in Hanby Lane adjoining Welton le Marsh and build the Alford Hanby hall in 1730. Firstly, this contradicts many of the statements made in the Wikipedia article referenced above, I would suggest that the long term owners of the building are likely to be the most accurate authorities on its history. Secondly, this confirms that members of the Hanby family were living in the area throughout and beyond the Civil War. They may not have been descendants of Sir William Hanby, which is why the land was passed by the Crown to Sir John Buck.

Font removed during dissolution

The font may have been removed and hidden during Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries to prevent its loss.

Whilst possible, this requires the assumption of an additional story, without any direct supporting evidence. If the villagers cared so much about this vital part of the church, why did it end up being left in a field as a cattle trough?

Church visitation

The inspection records of the church (visitation) in 1709 indicates that the church was still standing and in good condition. This presents the greatest challenge to the story.

Glebe Terrier 1674

Wee have neither parsonage house nor Vicarrage house, nor any Gleabe Lands, nor have uppon the best enquirye that wee can make by the Antient inhabitants of our Parish or any other Intelligence whatsoever.

The 1674 account bemoans the lack of any church property in the village (possibly an attempt to identify assets that might be used to fund the church rebuild?). It does not mention the condition or even existence of the church.

Churchwardens presentment 1709

Our Parish Church is in good and sufficient repair: only the porch thatch’d with straw, the Nave lead, the Chancel til’d, & all things decently order’d as become the house of God.

Most mediaeval churches in Britain were originally thatched (see https://thatchinginfo.com/thatched-churches-in-east-anglia/). It would therefore be possible that Welton church had been repaired and re-roofed following the Civil War siege damage, only for the roof timbers to fail under the additional weight sometime between 1709 and 1739.

What is the alternative?

The simplest explanation for the evidence found (Occam’s razor) is that the story of an English Civil War battle between Alford, Willoughby, Hanby, Boothby and Welton le Marsh are true and the siege of Welton le Marsh church really did happen. If this is not accepted, then an alternative scenario has to be found for:

- Why Welton le Marsh church is recorded as having fallen down before 1791, with the spire being the final part to collapse in 1791

- Why Thwaite Hall (1739) is constructed from the same medieval chalk and sandstone blocks as the church

- Why Welton le Marsh church and Thwaite Hall have musket ball marks, inside and out, on their walls

- Why it was that when Welton le Marsh church was reconstructed in 1792, there were not enough stone blocks remaining, so bricks had to be used

- Why the photographed Hanby Hall was built in the mid to late 17th century, given that it was the manor house for Hanby village which existed before 1348 (when it was recorded as deserted due to the Black Death)

- Why a new Hanby Baronetcy was created in 1660 when there were no living claimants to Hanby Hall

- Why musket furniture was found scattered around the grounds of Hanby Hall in the 1940s

- Why the medieval church font was found in a field near the church. If it was laying in the ruins of the church for a few months in 1791 between the spire collapse and the beginning of the rebuilding, it is unlikely anyone would have contemplated removing such a sacred object for agricultural purposes. Alternatively, if it had been laying in the rubble for over a hundred years with no obvious prospect of reconstruction and other villagers were plundering material (including to build Thwaite Hall in 1739), then it would seem quite reasonable.

- Why the font has several musket ball marks on it

- The village map of 1792 shows every building in the village, including a small chapel in the grounds of what is now Baytree House – except the church, suggesting it was not considered a building at the time.

Further research

The following activities are planned to collect more evidence:

- Metal detecting for musket balls and other non invasive techniques in Welton le Marsh church yard, with assistance from Horncastle History and Heritage Society https://horncastlehistory.co.uk/ (with support and approval from the Church of England)

- Records form the Church of England, indicating whether there was an interruption of Welton le Marsh services after 1643 (Investigation currently ongoing by Philippa Glanville and Trevor Oliver)

- Restoration work in Welton le Marsh church which may uncover historic fabric and physical evidence (Work currently ongoing by Trevor Oliver https://millstoneheritagetraining.org.uk/about-us)

- Consultation with English Civil war experts on the movement of troops around Lincolnshire in 1643, particularly ahead of the battle of Winceby. In particular the Battlefields Trust https://www.battlefieldstrust.com/ and Oliver Cromwell Association https://www.olivercromwell.org/wordpress/

- Cooperation with archaeologists on Eastern Green Link 3 & 4, digging alongside the site of Hanby Hall https://www.nationalgrid.com/the-great-grid-upgrade/eastern-green-link-3-and-4

- Presentation to the Royal Historical Society to encourage professional historians to join the investigative research https://royalhistsoc.org

Hugely enjoyed reading this,more to come I hope?

maybe the impending National GridArdent project in Welton ,with the legally required archaeological investigations,will reveal more clues in the form of military artefacts,horseharness or traces of earth works.

LikeLike

Absolutely fantastic research and amazing to read of such historic events in this sleepy little village. I hope we one day, in the not too distant future, get a commemerative plaque in the village in recognition of this battle just as Winceby has.

LikeLike