Thwaite Hall is a Grade II listed building, reputedly part of a former Augustinian Priory, with attached cottage; the present house dates from the 14th century.[6]

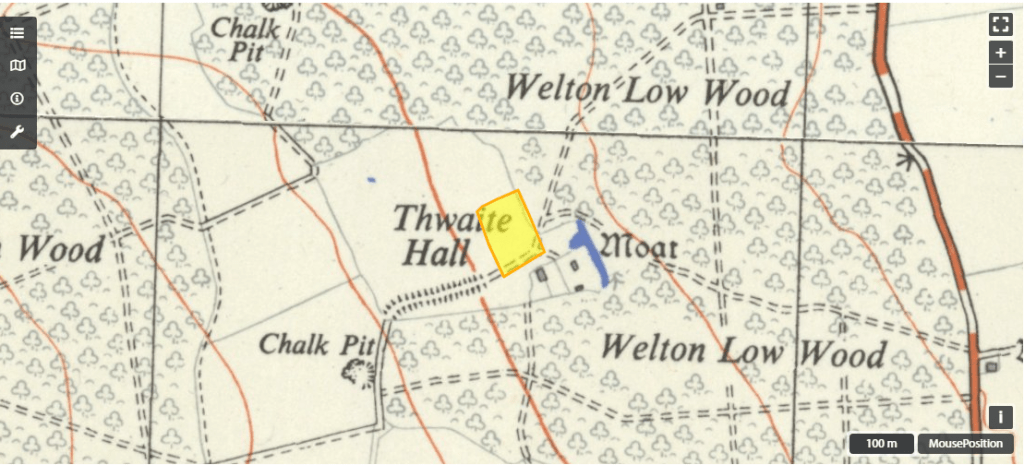

It stands in a wooded area to the North of Welton le Marsh and may have been surrounded by a moat. Other buildings formerly stood hearabout and are marked on the 1st edn OS 1″ map.

The current building is composed of two adjoining parts. On the south side is a traditional red brick Georgian house with features in Palladian and later styles. On the North side is a fascinating stone building known as Tudor Lodge.

Origins of the name “Thwaite”

Thwaite is derived from an Anglo Saxon word meaning a clearing in a wood. It is likely that this area of land has always been woodland.

Extracts from the history of Ormsby by W.O.Massingberd, refer in 1631 to Whait in the parish of Welton and later Whaite, which are presumably earlier spellings of Thwaite.

Susannah, baptized at Gunby 26 Oct 1606. She married first 4 Jan 1625 Richard Cater, gent., one of two sons of John Cater of Langton near Wragby and had two sons, Francis and John. Richard Cater was killed by the fall of his horse 10 Jul 1631 and buried in Welton Church. Susan Cater, widow, late the wife of Richard Cater late of Wait, in the parish of Welton, deceased, petitioned the Master of his Majesties Court of Wards and Liveries for the wardship of Francis Cater, an infant of seven years, seised of the reversion in fee simple of the grange of Waite and of the rectory of Welton, expectant after the end of a lease of 90 years made to Thomas Massingberd.

She married secondly 6 Oct 1635, Richard, second son of John Gedney, of Swaby, esqr.

Francis Cater had a son John, as appears from a certificate given to his father, Francis Cater, son of Richard Cater of Waite, in the parish of Welton, gent., by Sir William Massingberd, 24 Oct 1717, now at Gunby Hall.

Mary Massingberd married John Cater, as the following surrenders of the five acres of copyhold land, which she had inherited from her grandfather show:-

1658 Mary Massingberd, spinster, at the Court Baron held 11 Feb last surrendered 5 acres of pasture in Addlethorpe to the use of John Cater, gent., his heirs and assigns.

1658 John Cater and Mary his wife, surrendered 21 Feb last 5 acres of pasture in Addlethorpe to the use of themselves for their lives, remainder to the heirs of their two bodies

Tudor Lodge

A plinth runs round the East side and Eastern parts of the North and South walls. The South Western end is masked by an 18th Century brick cottage. On the East and South sides the courses below the offset are of early brick. The West end of the building is of later brick from c. 1.5m up.

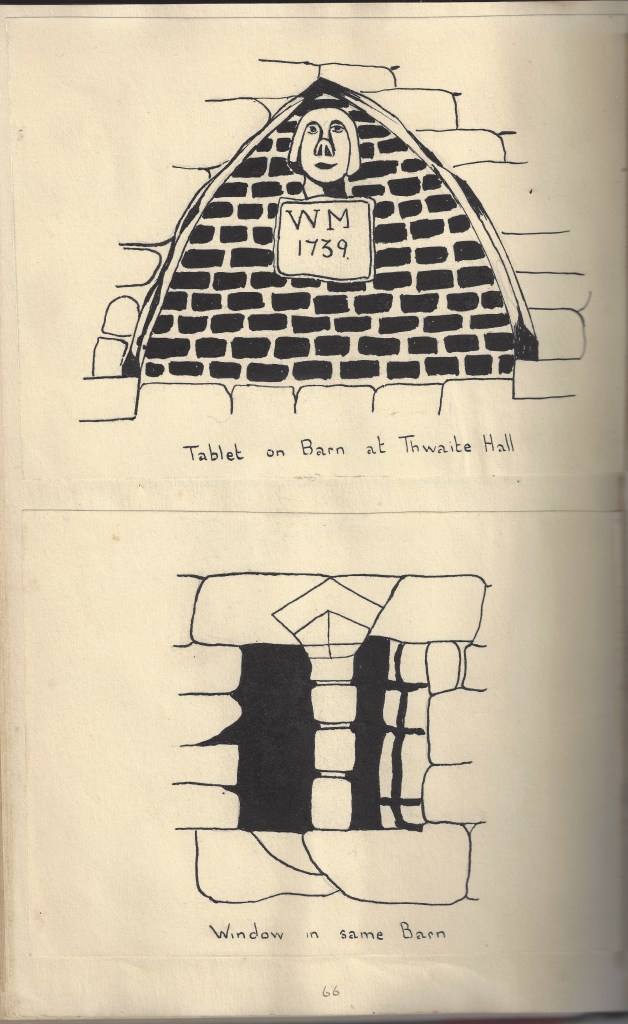

In the North wall is a doorway with a bricked up pointed head and remains of moulded bases inside and out. East of this on the ground floor is a mutilated splayed window. In the East wall, the only window is a large one at first floor level with a bricked up pointed head, a grotesque face and date stone “WM 1739” set into it. The South wall has three narrow blocked splayed windows set more or less equidistantly, with two more at first floor level. The more Westerly of these has been set up as a dovecote with brick divisions. The West wall shows no original features.

The character of the building is entirely domestic, but dating is hard to arrive at the in the absence of original architectural features. It need to be earlier than the 15th century, although the small windows may be hard to explain at this date. The datestone in the upper East window no doubt refers to restoration at this date as there is much brick patching.

Official listing

Historic England’s official grade II listing records:

Part of former Augustinian Priory, with attached cottage, now house. C14, C18 addition, with C20 alterations. Coursed squared chalk, red brick, pantile roofs, stone coped gables. 2 storey, single bay front with plinth, central planked door with pointed arched head. To left a small planked opening. To first floor a planked doorway. In the left gable a 6 glazing bar light with medieval arch over. In the brick tympanum a carved human head and datestone “WM 1739”, possibly the date of the attached C18 cottage at the rear, in red brick, with pantile roof having brick coped tumbled gables and stacks. 2 storey, 3 bay front with central panelled door covered by C19 gabled wooden porch, flanked by single glazing bar sashes in wider segmental headed openings. To first floor are 3 glazing bar sashes to eaves. Interior has 2 re-used ovolo moulded girders. An Augustinian Priory was recorded here in 1440.

Speculation on the history of Tudor Lodge

The name on the date stone “W.M”. may be William Massingberd of Gunby.

The building appears to be of the same chalk and Spilsby sandstone block construction as nearby St Martin’s Church in Welton le Marsh, therefore there may be a connection in design, timing and source of building materials with Thwaite Hall.

What do we know about the St Martin’s Church?

- The church was built on or before 1220, based on the list of vicars there.

- The Church tower is recorded as having collapsed in 1791.

- The lower half of the church appears to be medieval chalk and sandstone blocks from the original church. Some stones have carvings of coats of arms, which presumably were on the inside of the church originally. This suggests that the lower half of the church was rebuilt from stones remaining onsite (as opposed to leaving the lower walls in place).

- The upper half of the church was rebuilt from Georgian bricks. This suggests that the stones to make the original full height church were no longer available. One presumes that a stone church would have been more aesthetically pleasing than the two-tone stone and brick appearance. It is possible that half of the stones were too damaged in the church collapse to be reused.

What don’t we know about St Martins Church?

- The collapse of the church report does not mention whether the nave was still standing in 1791.

- Where did all of the stones used to build the original church go to? None seen to have been reused in the construction of any houses in the village.

What do we know about Thwaite Hall?

- In 1221 the Abbot of Thornton secured the advowson of Welton-in-the-Marsh in a suit with Walter de Hamby, a descendant of the original donor. Therefore, although the cell at Thwayte is only recorded in the fifteenth century, its origins may be two hundred years earlier.

- The Hall appears to be built from exactly same material as the church.

- Crop marks show evidence of a much larger building having existed there.

- Arthur Hundleby records the remains of a “Castle” on the rise just in front of the current hall. Presumably this can be taken that he saw large stone blocks in the ground.

- Historian Nikolaus Pevsner thought the stone building to be of much later origin (than the Augustinian cell), and rather just re-used material from the possible Augustinian structures on the site.

Assessment – putting the clues together

There are a at least two possible conclusions consistent with some or more of the facts:

- The church and hall were built 1220-21, by the same people using the same building materials. This may include the much larger buildings on site, the remains of which were plundered by Henry VIII. The current hall has been standing since 1221 (or fifteenth century when the presence of the cell was recorded) and was repaired with Georgian brick material and other remains of the cell in 1739. (Does not explain where the missing stone from the Church went to or Pevsner’s view that the hall is later the date of the cell.)

- The church nave collapsed before 1739. Some of the stones were used to build the current barn at Thwaite Hall. When the church tower collapsed in 1791, an effort was made to rebuild it using the remaining stone and Georgian brick in 1792. All of the material on site for the cell was cleared during the dissolution. This would explain what happened to the larger buildings.

Legends

There are tales told by many villagers about a tunnel that ran between the now-demolished Hanby Hall and Thwaite Hall. Whilst this is a common theme among many villages around the country, there are named second-hand accounts of its discovery. Watch out for a more detailed article to follow.

Georgian cottage

The Georgian cottage is physically joined to Tudor Lodge and in a curious internal arrangement, the Northern end forms part of Tudor Lodge’s living space.

Augustinian Cell

In 1221 the abbot of the Augustinian Thornton Abbey (see below for more detail), secured the advowson of Welton-in-the-Marsh. At some point a “monastic cell” (A small monastery or nunnery of the Augustinian order dependent on a larger mother house.) was built at Thwaite. The earliest record is from the fifteenth century, but it may have been built earlier.

One Canon served here in 1440 and the cell was still in existence in 1536 (up to the time of the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII)

Lincolnshire heritage record crop marks overlapping the current buildings, but over a much larger extent. They speculate that although these are of an unknown date, they be the footprint of the Augustinian cell.

Maps

Area of crop mark, showing potentially much larger building

(From OS 1st edition 1888)

William Hundleby’s account of Thwaite Hall (1938)

Situated in the middle of Welton Wood is an ancient farm-house known as Thwaite Hall. Little seems to be definitely known about the past history of this white-washed brick. The present structure is not of a great age – a little over a hundred years perhaps – but is obviously built on the site of much earlier buildings. In the moat which surrounds it, traces of early foundations have been found and a very old barn at the rear of the house contains a stone bearing the date of 1739, although the barn itself patched as it is would seem to be very much older than that.

In the rising ground in front of the house can be traced the foundations of an old “castle”. These, overgrown with grass are scarcely visible except after a very hot dry period when the grass is thin and low. Between this “castle” and Castle Hill in Hanby runs an underground passage which has only recently been blocked up and has been seen by many villagers.

“Thwaite” itself means a “clearing” and this would seem to be a very suitable name when it was given as indeed it is today. The wood surrounding it is gradually decreasing in size, being now with the low scrub land, at the most 600 acres in extent.

In the early days and up to till the latter half of the last century (C19), the wood was intersected by very narrow ridings or “haks” as they were called. These enabled the keepers to get fairly quickly from one “watch-house” to another. These were more or less permanent shelters for the keepers, but have since entirely disappeared.

There is one hak, much wider than the original ones which bears the name “Gideon’s Ride”. It seems that an old man named Frost who lived in a cottage just outside the wood was in the habit of walking home late. On one occasion he was frightened almost out of his wits by the sudden appearance of a stranger riding very fast behind him. Old Frost did not stop to examine the figure very closely, but saw him from the security of his cottage door, disappear into a hak. This happened on several occasions when our old friend was returning home late and always the rider disappeared into the same part of the wood, which soon came to bear the name “Gideon’s Ride”. History does not tell us where Frost had been to on these occasions. Perhaps if we new we should better be able to judge the truth of the matter!

Another point of interest in connection with Thwaite Hall and Welton Wood is the outline, clearly visible, of a road which once connected the Hall with the village. Known to a few older inhabitants as the “Hollow Road”, a shallow depression, with an average width of about 10 feet, can be traced right from the village. Sometimes it reaches a depth of about four or five feet, sometimes only as many inches, but traces of the original chalk surface can be found in many parts. This “road” is interesting as it probably skirted the wood and serves to indctae the boundary of Welton Wood in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth centuries. It remains, now, of course run through open ground.

Details of Thwaite Hall by Arthur Hundleby

Bibliography

J.Harris and N.Pevsner – Buildings of England; Lincolnshire 1964, P417

W.Page (Ed) – Victorian county history, Lincolnshire vol 2 1906 P.166

D.Knowles & R.Hadcock – Medieval Religious Houses, England and Wales 1971 pp144, 176

Ordnance Survey record card TF 46 NE 3

N.White – Lincolnshire Directory, 1856 p.537

Thornton Abbey, relation to Welton le Marsh and Thwaite Hall

Thornton Abbey, by David Wright – DSCF1751, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6073173

The abbey of Thornton was founded in 1139 by William le Gros, earl of Albemarle and lord of Holderness. The foundation charter states that by the counsel of his kinsman Waltheof, prior of Kirkham, of Simon earl of Northampton and Henry earl of Huntingdon, the founder placed here twelve canons from Kirkham who were at first ruled by a prior; and the house was raised to the dignity of an abbey by bull of Pope Eugenius III in 1148. (fn. 1)

Before 1284 the Albemarle estates escheated to the crown; but the canons of Thornton had already acquired the privilege of administering the estates of the monastery during voidance, without fees to the patron, except such as were due to two servants who kept the great gate and the door of the guest house in his name. This privilege was confirmed by the king, (fn. 2) who also, in consideration of a fine of £10, promised not to grant the advowson of the abbey out of his own hands and those of his successors. (fn. 3) It remained therefore a royal foundation until the dissolution.

The abbey was well endowed with lands and churches by the founder and other benefactors; and in 1291 its temporalities were taxed at £235. (fn. 4) The original number of canons was considerably increased, and even at the dissolution there were still twenty-three.

In 1221 the abbot secured the advowson of Welton-in-the-Marsh in a suit with Walter de Hamby, a descendant of the original donor. (fn. 5) From 1269 to 1292 a good deal of expense was incurred by the purchase of certain manors and advowsons. (fn. 6) In 1275 the abbot was accused of appropriating sixteen acres on the moor of Caistor for his sheepfolds (fn. 7); in 1319 he received a pardon for his trespass. (fn. 8) During the reign of Edward II the canons of Thornton had to contribute provisions for the Scottish war at considerable expense, and were also disseised of some property by Hugh le Despenser, of whose want of reverence for church property this is not the only instance. The land was restored by Edward III, and payment promised for the provisions. (fn. 9) In 1332 losses from inundation, cattle plague, and the burden of hospitality led to the impropriation of the church of Wootton. (fn. 10) Several pensioners were sent successively by Edward I and Edward II to spend their last days at the abbey. (fn. 11) In 1312 the abbot was summoned for the first time to Parliament, but he and his successors made great efforts to escape this duty; in 1341 an exemption was formally granted, (fn. 12) but in 1348 it was revoked, and attendance was thenceforward required. (fn. 13) A petition made by the abbot in 1341, that he might not have to pay a ninth on his temporalities as well as the annual and triennial tenths, was granted for all property acquired before 1292. (fn. 14)

Some of the abbots of the fourteenth century were great builders, and spent on the decoration and improvement of the monastery rather more than their revenues justified. William Grasby, abbot from 1323 to 1347, incurred great expenses in this way; he also purchased the manor of Barrow for £200 and the advowson of Welton for £60, and at his death the house was evidently somewhat embarrassed; (fn. 15) and the bursar at this time was extravagant and suspected even of dishonesty. (fn. 16) The next abbot, Robert of Darlington, spent a good deal on the decoration of the church and monastic buildings generally. (fn. 17)

Little is known of the history of the abbey in the fifteenth century, except that it shared in the general decline of learning and discipline. (fn. 18) Its prosperity, however, was not much diminished. In 1518 the abbot was able to secure from Pope Leo X a bull granting him the privilege of celebrating mass in a mitre with gold plates and full pontificals. (fn. 19) The abbey was described in 1521 as one of the goodliest houses of the order in England. (fn. 20) Some slight losses were suffered by inundation in 1534; (fn. 21) but the revenue was returned in the same year as nearly £600 clear.

Abbot John Moor signed the acknowledgement of supremacy, with twenty-three canons. (fn. 22) He was accused after the Lincoln rebellion of having provided the insurgents with money; (fn. 23) but he was not brought to trial. His successor, William Hobson, surrendered the abbey in 1539, receiving a pension of £40. The canons received annuities of £5 to £7 each. (fn. 24) The revenues of the house were employed for a short time in maintaining a college for secular priests. (fn. 25)

From the thirteenth century onwards this house was one of the largest and most important in the county. There is no precise record of the number of canons in its most prosperous days, but the order of Bishop Alnwick that one canon out of twenty should be maintained at the university looks as if there were more in his time than at the dissolution. The Chronicle transcribed by Tanner gave lists of obedientiaries which imply a very considerable household. (fn. 26) A school of fourteen boys, who had to serve at mass, was kept in the almonry, with a master to instruct them, and a large number of corrodyholders claimed maintenance from the Court of Augmentation at the surrender of the monastery. (fn. 27)

The house had its vicissitudes, as might be expected, in point of order and discipline. The abbot of Thornton was one of those deposed by Bishop Grosteste in 1235 for causes not specified. (fn. 28) There were cases of apostacy and other individual delinquencies from time to time. In 1298 a canon named Peter de Alazun, having a greater zeal for learning than for holy obedience, forsook his monastery and joined the scholars at Oxford in secular habit. He was excommunicated by the chancellor throughout the schools, but apparently did not repent and return till 1309. (fn. 29) Another canon, Peter Franke, was involved in 1346 in a discreditable fracas between the servants of the monastery and those of a knight of the neighbourhood. The knight’s servants had seized a boatload of victuals on its way to the abbey, and Peter, being the knight’s kinsman, thought he could induce them by fair words to give up the booty; but though he urged the ringleader ‘in the sweetest possible way’ to restore the boat, he was answered in such rude fashion that he lost his temper, snatched up the nearest weapon, and wounded the man mortally. The Earl of Lancaster interceded for the canon, who would naturally for this act have been disabled from exercising any ecclesiastical function; and the pope allowed him to retain the exercise of minor orders, and to hold a benefice. (fn. 30)

Cases of this kind show us nothing of the general condition of the house. (fn. 31) The abbot at this time was William Grasby, who was at any rate zealous for the exterior adornment of the monastery, (fn. 32) and his appointment jointly with the prior of Kirkham in 1340 by Pope Benedict XII to convoke a general chapter of the order (fn. 33) seems to imply that he enjoyed a good reputation among his brethren. The next abbot, Robert of Darlington, had been made cellarer previously by Bishop Gynwell expressly on account of his ‘honest and laudable conversation,’ (fn. 34) and an order given during his time that ‘no woman, however honest,’ should be allowed to live in the monastery, (fn. 35) does not necessarily imply that any serious wrongdoing had been discovered. His successor, Thomas Gresham, was however a man of very evil life, (fn. 36) and those who followed for a while, though less unworthy of their office than he, do not seem to have been capable of restoring the credit of the house. Bishop Flemyng’s injunctions in 1424 show that the number of boys educated in the almonry had diminished, and that the poor and infirm were not succoured as in days gone by. (fn. 37) When Walter Moulton succeeded in 1439 he was evidently quite unable to cope with the laxities and disorders of the house. At Bishop Alnwick’s visitation of 1440 he complained that the obedientiaries did not render their accounts. The canons said that the abbot was thoroughly incompetent, that manors, granges, &c., were let without consent of chapter, that the sick were not provided for, that there were only two boys in the almonry, and no scholar at the university. The brethren did not eat regularly in the refectory, and the sacrist had lent the sacred vestments to seculars for games and spectacles. The bishop’s injunctions ordered reform on all these points: after personal examination of the abbot, he appointed him a coadjutor elected by the convent. (fn. 38)

After this the house seems to have recovered a higher standard. Bishop Atwater in 1519 had no remarks to make at all. (fn. 39) Nothing is alleged to the discredit of the abbot and convent at the end, except sympathy with the popular movement in 1536; and even if this is true, it does not prove that there was anything wrong in the lives of the canons.

The original endowment of the abbey of Thornton by the founder consisted of the vills of Thornton, Grasby, Audleby, Burnham, ‘Helwell’ (Linc.), and Frodingham (Yorks.), with the churches of Audleby, Ulceby, Frodingham, Barrow-on-Humber, ‘Heccam’ and ‘Randa.’ Other benefactors added the vill of Humbleton and half that of Warham, with divers other parcels of land, and the -churches of Thornton, (Linc.), Humbleton, Garton, Welton, and half that of Wyner (Yorks.), and ‘Ulstikeby.’ (fn. 40) The patronage of the churches of Carlton, Kelstern, Worlaby, and Wootton was acquired later, with the manors of Halton, Barrow, and Mersland. (fn. 41)

The temporalities of the abbey were taxed in 1291 at £235 0s. 9d. (fn. 42) In 1303 the abbot held a knight’s fee in Wootton and Goxhill, another in Barrow, one and a half in Killingholm, a half in Owmby and in Wootton and Little Limber, one quarter in Worlaby, and smaller fractions in Barton, Croxton, Killingholm, Searby, Welton, and Great Sturton. (fn. 43) In 1346 his lands were almost the same, except that he had two fees in Barrow (fn. 44); in 1428 he had a small fraction of a fee in Hamby as well. (fn. 45) In 1431 he held the manors of Barrow and Ulceby, acquired since 20 Edw. I. In 1534 the clear revenue of the abbey amounted to £591 0s. 2¾d., and in the Ministers’ Account of the year 1542-3 includes the churches of Thornton, Barrow, Ulceby, Worlaby, Wootton, Carlton, Kelstern, and Grasby in Lincolnshire, Elstronwick, Danthorpe, Garton, and Hinton in Yorkshire, and the manors of Thornton, Wootton, Barrow, Carltonle-Moorland, Halton, Killingholme, Gothill, Ulceby, Owersby, and Stainton-le-Hole in Lincolnshire, and Garton, Ottringham, Frodingham, Humbleton, Faxfleet, and Wyncetts in Skeffling (Yorks.). (fn. 46) There was a small cell of this abbey at Thwayte, in Welton in the Marsh, of which a single canon had charge, during the fifteenth century. (fn. 47) =

Very interesting and detailed. Thank you very much Alex.

Kind regards

<

div>Mary Robson

Sent from my iPad

<

div dir=”ltr”>

<

blockquote type=”cite”>

LikeLike