Welton le Marsh features in three entries in the Domesday book, which recorded land ownership across England in 1086 by the orders of King William I, the Conqueror. The mediaeval Latin language used can be difficult to understand so please see the guide below. Note that the land was split between three landowners.

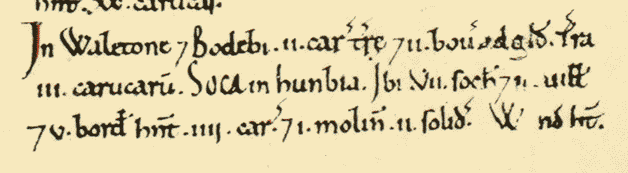

Land of Ivo Taillebois

(Manor house Hanby Hall)

In Waletone and Bodebi [Welton le Marsh and Boothby in Welton (Candleshoe)] there are 2 carucates and 2 bovates of land [assessed] to the geld. There is land for 3 teams. It is soke [has an outlying dependency] in Hunbia [The lost village of Hanby in Welton le Marsh]. 7 sokemen, 2 villeins and 5 bordars have 4 teams and 1 mill rendering 2 shillings. W nd [sic] has it.

The tenant-in-chief in 1086 is recorded as Ivo Tallboys, but we know this to be a millennium-old documentation error as it is the Old English phonetic spelling of Ivo Taillebois, one of the generals of King William 1.

Households. The Lord of the Manor in 1086 was Wimund (which is a Saxon name and unusual as many Saxons were dispossessed of their lands by the Norman invaders).

The village of Hanby, Lincolnshire is mentioned above. The village name has a Norse-Viking pre 9th century origin and translates as ‘Hundi’s farm’ with ‘Hundi’ being a personal name of the period. The village name is recorded several times in the 1086 Domesday Book as ‘Hundebi’

You can the whole page on Open Domesday at https://opendomesday.org/book/lincolnshire/32

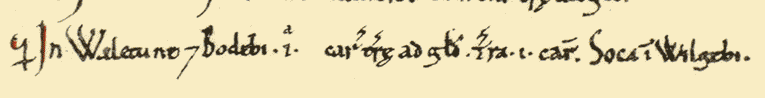

Land of Gilbert of Ghent

(Manor house Boothby Hall)

In Waletune and Bodebi [Welton le Marsh and Boothby in Welton (Candleshoe)] there is 1 carucate of land [assessed] to the geld. There is land for 1 team. It is soke [has an outlying dependency] in Wilgebi [Willoughby].

The tenant-in-chief in 1086 was Gilbert of Ghent. The Lord of the Manor in 1086 was Roger (a Norman name) but in 1066 was Tonni a Saxon, probably indicating that he had been evicted.

You can the whole page on Open Domesday at https://opendomesday.org/book/lincolnshire/39/

Land of Jocelyn, son of Lanbert

(Manor house – the Old Post Office)

S. In Waletone and Bodebi [Welton in the Marsh and Boothby (Candleshoe)] there are 2 carucates and 2 bovates of land [assessed] to the geld. There is land for 3 teams. It is soke [has an outlying dependency] in Clasbi [Claxby]. Rayner, Gocelin’s man, has half a team there [in demesne], and 14 sokemen have 3 teams.

The tenant-in-chief in 1086 was Jocelyn son of Lambert. The Lord of the manor in 1086 was Rainer (A Norman name), whilst in 1066 it was the dispossessed Saxons Aghmund (son of Walraven).

You can the whole page on Open Domesday at https://opendomesday.org/book/lincolnshire/48/

Meaning of the terms used in Domesday

The Domesday Book offers great insight into life at the time of the Norman Conquest. When you read through the records contained in the Domesday Book, you run across a great many terms which may be confusing, such as ‘bordars’, ‘geld’, ‘hundreds’, and so on. This short glossary of terms is intended to help you better understand the terminology of the Domesday Book.

Acre

The Norman acre was a unit of measure of both length and area. It was defined by the length and width of a furrow — 40 by 4 perches. This was by no means a standardised measurement as a perch varied in length. (see ‘Perch’ below) However, assuming a perch equivalent to 16.5 feet, a Norman acre could theoretically match the size of a modern acre of 43,560 square feet: the equivalent Norman acre would be 660 feet long and 66 feet wide. An acre could be used as a value to assess geld, with 120 acres equalling one Hide.

Boor

A peasant of low standing. This term was on the way out, to be replaced by ‘Villan’.

Bordar

A peasant, lower on the social ladder than a Villan.

Bovate

One-eighth part of a Carucate.

Cartage

The obligation of providing carts for the transportation of a Lord’s goods.

Carucate

An area of land equal to the amount that could be worked by a team of eight oxen. In some areas, the Carucate was the measure used to assess geld, instead of the Hide.

Demesne

Land in the personal possession of a Lord, used to support that Lord rather than the tenants working it.

Free Man

A landholder of non-noble status. Freemen were often in the command of a Lord.

Furlong

A unit of measure equal to the length of a ploughed furrow, or 40 perches long.

Geld

Tax, assessed per hide.

Hide

The standard unit of land measure, used to assess geld (tax). In theory each hide was divided into four equal parts, called Virgates.

Hundred

The largest administrative division of a Shire. The Hundred was nominally 100 hides, but in practice the size of a Hundred varied widely from place to place.

Manor

An estate. Manors could be vastly different in size, and might have an official lord’s residence, or castle, at its centre.

Mill

Usually a corn mill for grinding grain, powered by water. Windmills did not come into use until well after the Conquest.

Perch

A measure of land varying from 14 to as much as 28 feet.

Plough

One way of assessing the value of an estate was to estimate the number of eight-ox plough teams needed to cultivate the land. Thus, a Domesday entry might say a ‘Then as now, 2 1/2 ploughs”, meaning that there was enough land on the estate to require 2 1/2 ox teams to work it. This measure could also be used to assess the value of the estate for taxation.

Render

A payment (usually payment in kind, such as livestock or grain). Render was sometimes used to determine the value of a manor.

Soke

The right to administer a given place and its people

Sokeman

A free man owing service to the Lord of a Soke

Sheriff

The royal official in charge of a Shire. The Sheriff was responsible for financial and judicial administration, as well as overseeing royal castles and estates in the Shire.

Shire

An administrative district, roughly equivalent to our modern county. The term Shire might also refer to the Court of that county.

TRE

Shorthand for the Latin phrase Tempore Regis Edwardi, which translates loosely as ‘In the time of King Edward’. Generically used to indicate the state of things before the Norman Conquest in 1066.

Villan

The nominally free inhabitant of a village, a villan (or villein) was better off than a bordar.

Wapentake

from Old Norse vápnatak, an administrative division of the English counties of York, Lincoln, Leicester, Nottingham, Derby, and Rutland, first clearly referred to in 962/963 and corresponding to the “hundred” in other parts of England. The term wapentake is of Scandinavian origin and meant the taking of weapons; it later signified the clash of arms by which the people assembled in a local court expressed assent. Danish influence was strong in those English counties where wapentakes existed.

A note about Administrative districts

For the purposes of taxation there were essentially three levels of administrative districts in Norman England. In descending order of size and importance these were the Shire, the Hundred, and the Vill, corresponding very roughly to our modern Counties, local districts, and towns/villages.

Definitions taken from https://www.britainexpress.com/History/domesday-terms.htm

Landowning in the feudal period

Domesday Book is largely about landowners and their estates, both before and after 1066. It represents Anglo-Saxon and Norman landholding in very different terms. The nature and terminology of landholding in 1086 is relatively straight-forward. Domesday Book has been called a ‘blueprint for a feudal society’, an observation prompted by a structure which represents landed society after the Conquest as based strictly upon tenure: tenants-in-chief held their fiefs from the Crown, tenants held manors from tenants-in-chief, and the occasional subtenant held his manor from the tenant immediately above him on the feudal ladder. Every man had his lord, and his lord was the man from whom he held his land, very probably the lord who had granted him that land within living memory. It was a structure of great simplicity, and for a generation or two bore some relationship, if distant at times, to the real world.

The nature and terminology of Anglo-Saxon landholding, on the other hand, are less easy to grasp and were expressed in a bewildering variety of formulae. In essence, Anglo-Saxon lordship was based upon personal bonds rather than land tenure, though tenure did enter into some relationships. The predominance of personal ties was simply a reflection of the fact that Anglo-Saxon landed society had deep roots. Most landowners would have inherited their estates, and few probably knew how their ancestors came by them. Lordship – a legal requirement on all men – was therefore a matter of choice, a bond of commendation forged from self interest: lords needed men to serve them, men needed patronage and protection. Anglo-Saxon lordship was of the bastard feudal variety into which Anglo-Norman society would quickly evolve.

In these circumstances, the wholesale disinheritance of the English landed classes after the Conquest was bound to give rise to disputes over title. A Norman granted the estates of one Anglo-Saxon magnate was tempted to treat the estates of that magnate’s men as part of the grant. Others might claim the estates of the same men on different grounds – that they were dependencies of manors owned by another Anglo-Saxon magnate, for instance. There were practical reasons, therefore, for collecting data on Anglo-Saxon landholding in 1086; but the complexity, variety, and inconsistency of what was collected showed that the commissioners struggled with this task and in some circuitsabandoned the attempt entirely.

For more detail, see Sir Fredrick Pollock and F.W. Maitland, The history of English law before the time of Edward I (second edition, 1898); Susan Reynolds, Fiefs and vassals: the medieval evidence reinterpreted (1994); and Judith A. Green, The aristocracy of Norman England (1997).

(Information from the Hull Domesday project https://www.domesdaybook.net/domesday-book/data-terminology/landholding/landholding-concepts )

1 thought on “Welton le Marsh in Domesday”